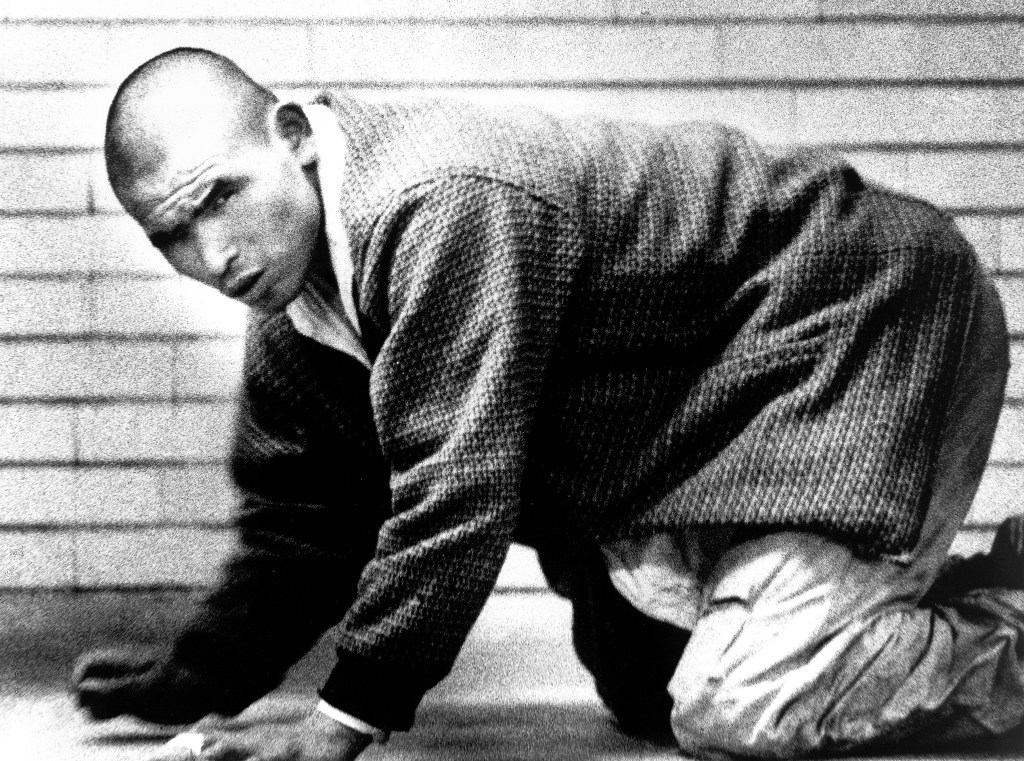

Photo Elysée in Lausanne presents an immense Japanese artist: over 60 years, Daido Moriyama has produced images that speak louder than words: his visual vocabulary chronicles the pace of change of Japan in the aftermath of its defeat in the Second World War. At a time endangered by image-overload and fake news, his fiery artistry stops our gaze and takes on a spectacular relevance.

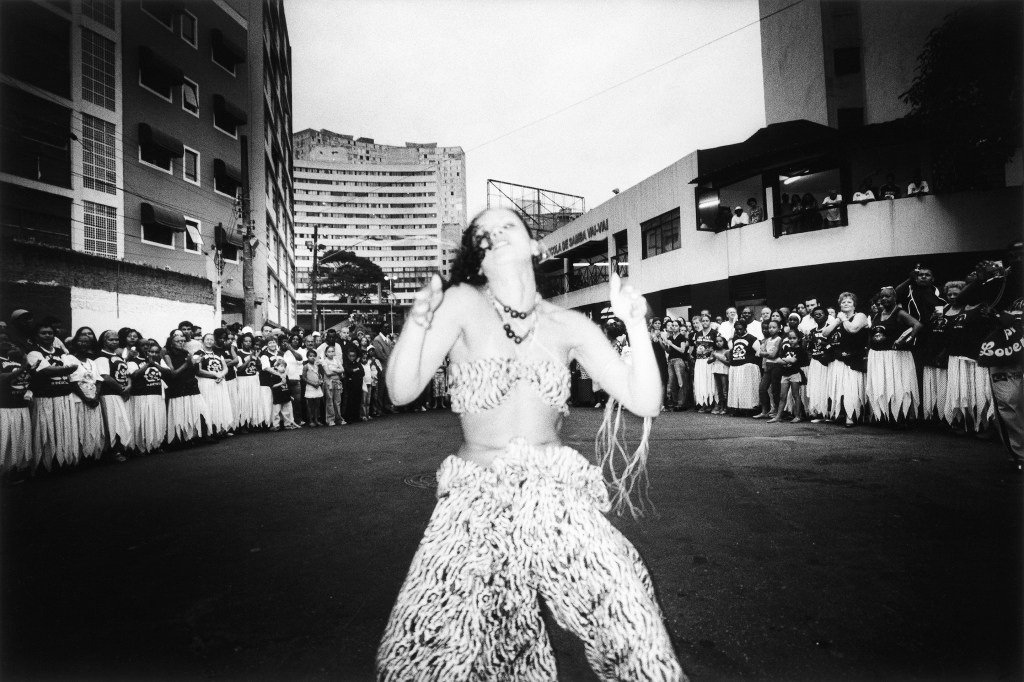

A major retrospective of Daido Moriyama’s works comes to Lausanne after Sao Paolo, Berlin, Helsinki and London, where The Guardian hailed it as the best photography exhibition in London in 2023.

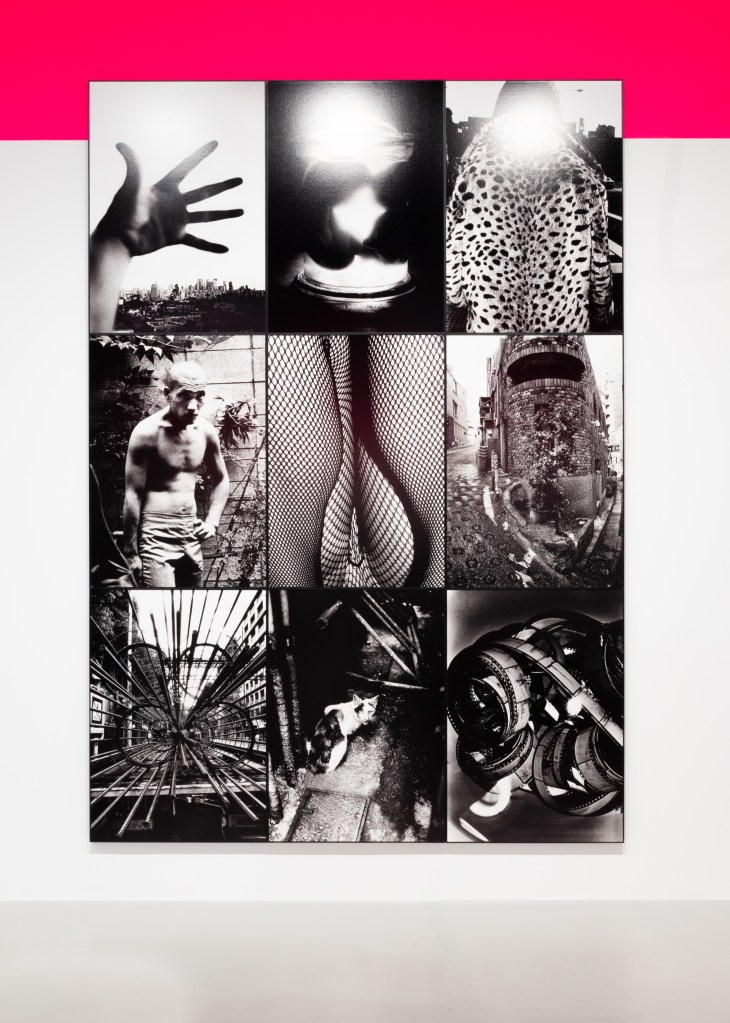

Thyago Nogueira, head of the contemporary photography department at Instituto Moreira Salles, Sao Paolo, Brazil, in collaboration with the Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation in Tokyo, has curated a stunning and powerful show: the photos are splashed like mosaics onto the Elysée walls.

The power of understatement

“I wanted to express the vitality and beauty of his work in a museum,” Nogueira explained when we met in Lausanne.

“I realized Moriyama wasn’t interested in single photos. He explained that images have different incarnations on different supports. He asked me: How do we bring them energy?”

The result is a walk through the streets of postwar Japan, but not in a documentary sense, nor does Moriyama aim to create iconic images, unlike the celebrated French street photographer, Henri Cartier Bresson, who seized scenes for their lasting power. Moriyama ‘s photography does not attempt to linger, as if the captured moments still belonged to the persons he has photographed. He makes no attempt to frame and compose, he just shoots.

“Get outside. It’s all about getting out and walking. That’s the first thing. The second thing is, forget everything you’ve learned on the subject of photography for the moment, and just shoot. Take photographs—of anything and everything, whatever catches your eye. Don’t pause to think.” DM

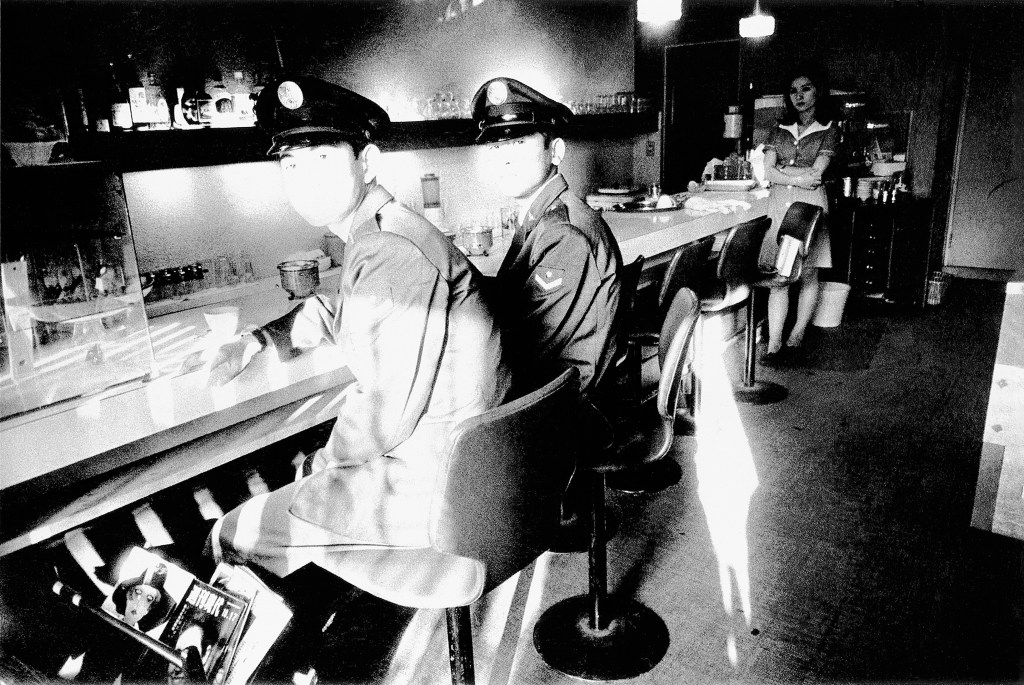

American culture of the Sixties

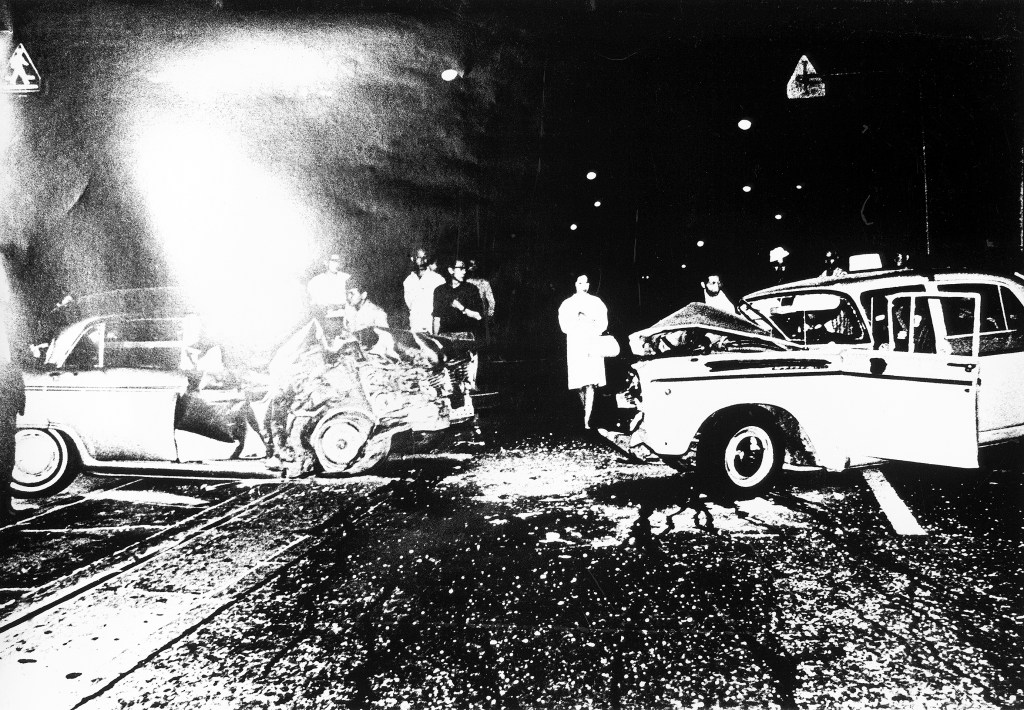

Born in Osaka in 1938, Moriyama moved to Tokyo in the early Sixties, when Japan was still under US military occupation and where the young photographer came under the influence of American pop culture. Andy Warhol’s legendary 1968 exhibition at the Modern Museet in Stockholm made a lasting impression on him.

Moriyama’s car crash series, and lines of tinned goods, are undisguised references to Warhol. But it wasn’t so much imitation, as it was an invitation to observe. In his early work for the avant-garde (and short-lived: 1969-70) magazine Provoke, Moriyama captured the sensationalism and consumerism of his times – kidnappings, celebrities, road accidents. He was exploring the manipulation and exploitation of private lives by the media.

“He reflects on the consumption of images and challenges the role of media,” says Nogueira. “At the same time, he enters into the living experiences of his subjects.”

“What we photographers can do, and should do, is capture with our own eyes those fragments of reality that are completely impossible to capture with existing words and continue actively to create materials which confront those words and thoughts.” Provoke #️2, editorial.

On the road

“Japan was moving fast, and we wanted to reflect that in our work.” DM

An intriguing paradox of Moriyama is his ability to embrace the American influence, while remaining so profoundly Japanese. The Beat Generation novel of Jack Kerouac, On the Road, published in 1957, sent Moriyama out onto the roads and highways of Japan where he led the existence of an image hunter and nomad.

“In those days, you never saw anyone out on the streets with a camera around their neck. I felt like I was doing something really way out and original. I never imagined I’d end up doing it – essentially living on the streets – for the next few decades.” DM

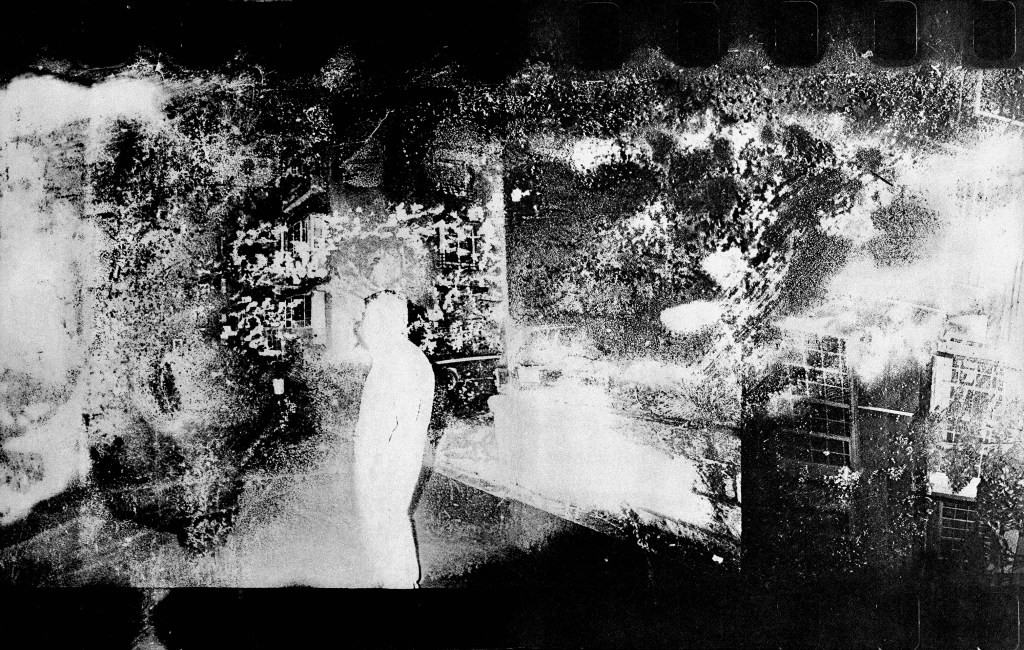

A new visual vocabulary

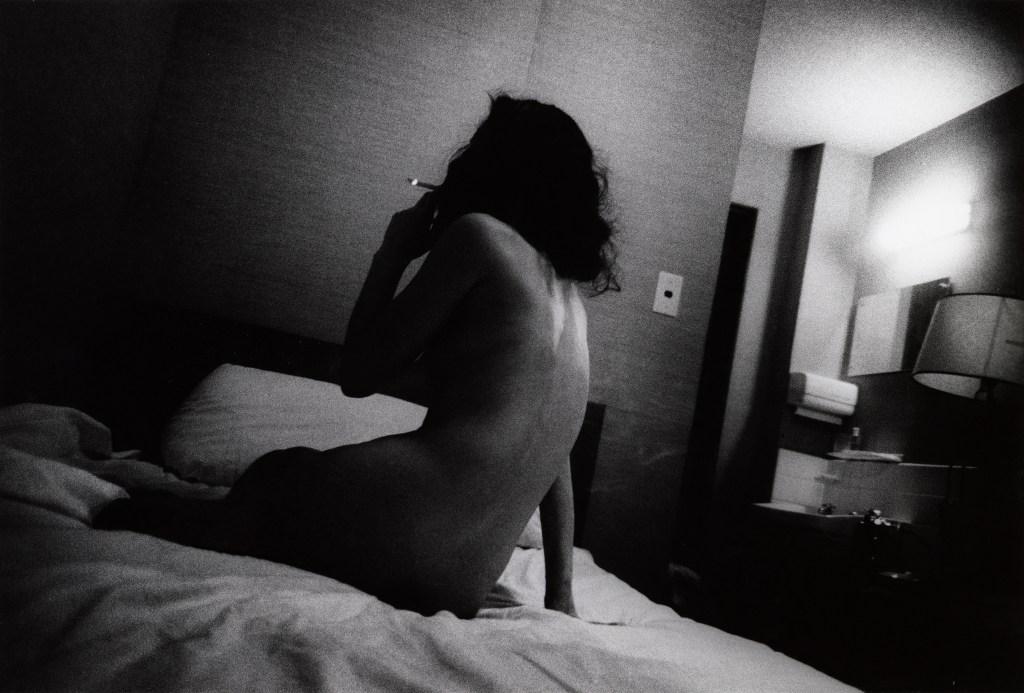

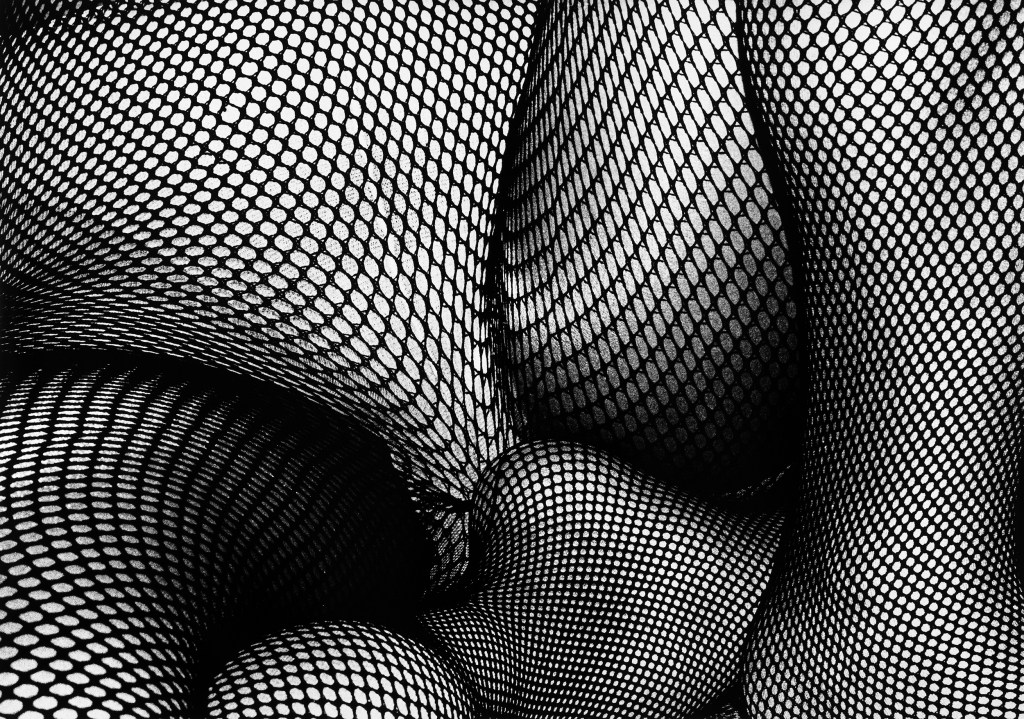

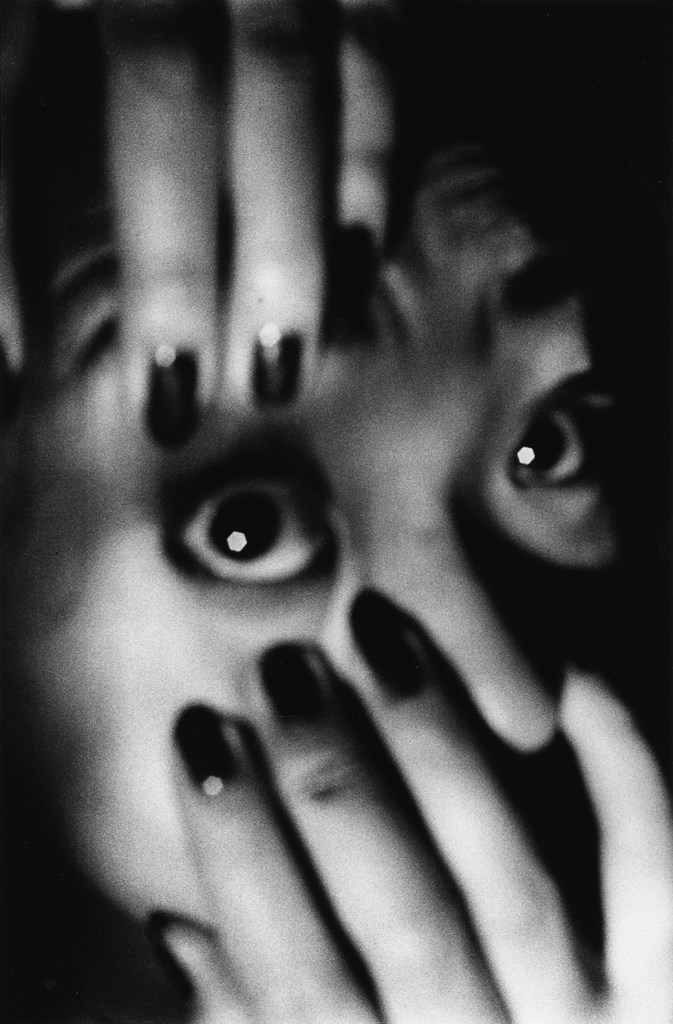

To create a distance between a picture and what it represents, Moriyama developed a unique aesthetic in black and white, defined by the Japanese catchphrase ‘are bure boke’ (grainy, blurry, out of focus). This gives an almost abstract quality to his work.

“Rather than sharpness and clarity, Moriyama delivers a subjective and personal experience,” Nogueira details. He suggests that his approach is highly philosophical.

Japan was able to offer a different thinking of image-making, explains the curator, because it was free from the weight and restrictions of the market. Nogueira considers Moriyama a radical conceptual artist who explores the political power of photography.

“Instead of a transparent window; we are looking at different ways of seeing reality. Moriyama singles out images to offer us a grammar to work with, a new vocabulary to think,” Nogueira insists.

“For me, photography is not a means by which to create beautiful art, but a unique way of encountering genuine reality.” DM

Memories of a Dog

In his seminal autobiographical memoire, Memories of a Dog, first published as a continuous narrative in the Japanese publication Asahi Camera in 1983, as well as in his successive writings, Moriyama delivers a few clues to his approach:

“When I take photographs, my body inevitably enters a trancelike state. Briskly weaving my way through the avenues, every cell in my body becomes as sensitive as radar, responsive to the life of the streets.” DM

“I have always felt that the world is an erotic place… For me cities are enormous bodies of people’s desires. And as I search for my own desires within them, I slice into time, seeing the moment. That’s the kind of camera work I like.” DM

Thyago Nogueira suggests that Moriyama’s approach is highly philosophical.

A walking retrospective

The beauty of the retrospective is that it creates a path through the successive periods of Moriyama’s life as a photographer and that we follow him, as if by his side. You can hear the bustle of the streets. It hardly matters that the photos are in black and white, and even his colour period in the early Seventies is like a ribbon of continuity.

An additional intimacy comes from the numerous publications that Moriyama has either published or inspired that lay in showcases or on consultation tables along the way, like stepping stones into his endless investigations. The artist famously admits that he is not interested in the layouts of his work, which he leaves to others.

The exhibition ends with an immersive overview of more than a thousand photos in the 57 issues to date of Record, Moriyama’s ongoing diary of urban explorations. As the images scroll rapidly on three screens, we are startled to discover that he is not telling stories, he is leaving us to decide what to do with the pictures. That’s why I call him an image whisperer.

“If an image is good, it is brought back to life by the feelings of the viewer.” DM

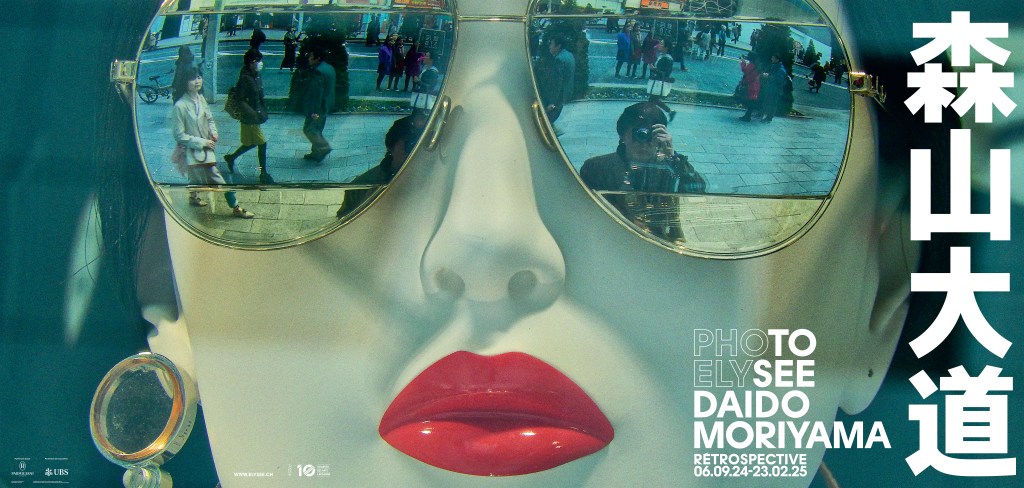

06.09.2024 – 23.02.2025

In collaboration with Images 2024, the visual arts biennale in Vevey, Moriyama’s iconic self-portrait, taken in the reflection of the sunglasses of a shop-window model (see above), was shown in a gigantic format on the outside of the Hotel des Trois couronnes.

Discover more from art-folio by michèle laird

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.