The country where Dada was invented celebrates the centenary of Surrealism in the three museums of Plateforme 10 in Lausanne. But why did Dada, one of the most influential art movements of the 20th century and precursor of Surrealism, all but disappear from Switzerland after it was launched at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916? In an exclusive interview, Fine arts museum director Juri Steiner sets the record straight.

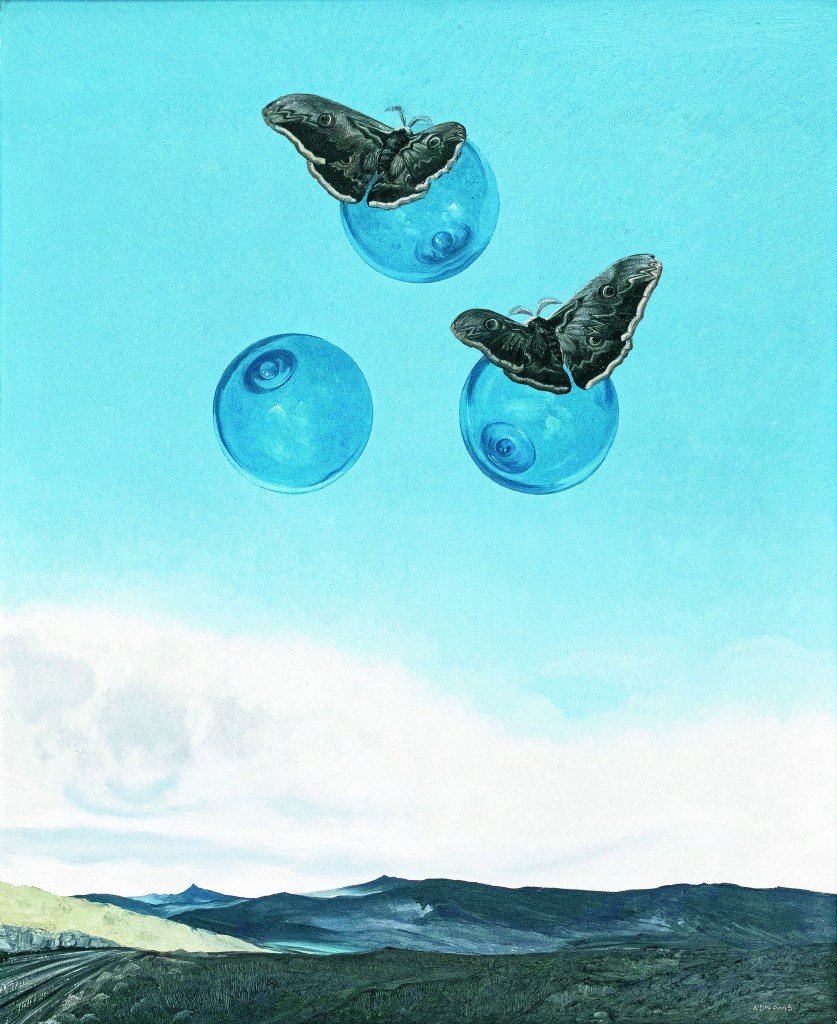

Marion Adnams, Emperor Moths / Thunder On the Left, 1963

Article published in an edited version by Swissinfo.ch from 18 to 30 June 2024 in the following languages (7):

English Switzerland, Dada and 100 years of Surrealism reproduced in Geneva Times

French La Suisse, Dada et cent ans de surréalisme

German Die Schweiz, Dada und 100 Jahre Surrealismus

Italiano La Svizzera culla del Dada e i 100 anni del Surrealismo

Español Suiza, el dadaísmo y 100 años de surrealismo, reproduced in ESEuro

العربية حركة “دادا” السويسرية… 100 عام من الفنّ السرياليّ

Русский Швейцария, дадаизм и столетие сюрреализма

This is the original version, based on an interview with Juri Steiner on 24,04. 2024. The integral transciption (in French) is published separately.

Chess is the starting point of the section “Creative strategies” in the Surrealism exhibition co-curated by Juri Steiner at MCBA. Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), a pioneer of Dada, was devoted to chess, as were Francis Picabia and Man Ray. View of the exhibition,

Etienne Malapert, MCBA.

The birth of Dada

The Dada art movement was born of the disillusion of avant-garde artists who found refuge in Switzerland during the First World War. Pacifists, or deserters, they denounced what Steiner calls the “bankruptcy of rationality” by means of the absurd (poetry, collages, songs, performances and painting).

The spirit of Dada rapidly spread to Europe and to the United States and became the prelude to Surrealism launched by André Breton by manifesto in Paris in 1924. But in Switzerland, it quietly disappeared.

The iconic Cabaret Voltaire, where Dada was born, languished for decades as a pub cum dance club, where non-conformist artists would give the occasional performance. Meanwhile, Dada-inspired art movements continued to emerge abroad, namely the Nouveaux Réalistes (new realists), Situationism, Lettrism and Fluxus, the latter sometimes referred to as Neo-Dadaists.

Juri Steiner, who co-curated the landmark “Universal Dada” exhibition in Zurich’s Landesmuseum in 2016 and this year’s “Surrealism, Le Grand Jeu” in Lausanne, shares his views on why it took so long for Dada to resonate in Switzerland again.

Juri Steiner (b. 1969) directed the Zentrum Paul Klee (ZPK) in Bern from 2007 to 2011. Doctor in philosophy, he has worked as a freelance art critic for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and freelance curator at the Kunsthaus Zürich, and set up the Arteplage Mobile du Jura for Expo 02. Since July 2022, he heads the Musée cantonal des beaux arts (MCBA – Lausanne Fine Arts Museum). Photo Cyril Zingaro.

The Dada marketing machine

The artists who had invented Dadaism all dispersed after the war, with only a few remaining in Switzerland. The survival and success of Dada, Steiner explains, owes a great deal to the promotional talent of Tristan Tzara, a Romanian writer and co-founder of the movement who moved to Paris in 1919.

Tzara built the first avant-garde network by means of all the communication methods at his disposal (letters, telephone, telegraphs, and flyers).

“He set a remarkable marketing machine in motion. We take our global view of art today for granted, but that was not the case before the Dadaists and Surrealists turned communication into an art form in itself.”

Punk, Dada’s grandchildren

Switzerland waited until May 1980 for a profound cultural change to take place that would rekindle the spirit of Dada. In protest to a large grant for the renovation of the Zurich Opera house, to the detriment of a planned Rote Fabrik cultural centre, “the grandchildren of Dada”, as Steiner calls them, took to the streets in a massive rebellion against the establishment. Known as Züri brännt (Zurich is burning), it marked the beginning of an alternative youth movement.

“To be an artist in Zurich was no longer to drink wine, wear a beret, pretend to be Max Bill and be part of the Zürcher Konkrete movement, which was the most important at the time.”

The Zürcher Konkrete movement (Zurich Concrete art) grew out of the theories on geometrical abstraction formulated in the 1920s by the protean Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg (also an early Dadaist who poached students from the Bauhaus). First adopted by Johannes Itten and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, it was later developed by the Swiss artist and designer Max Bill (pictured) and became the dominant art movement in Switzerland. The use of pure colours and geometric forms was later qualified as cold abstraction. KEYSTONE

To make their claims for autonomous arts centres, the rioters used new forms of media – video, collages, graphic flyers – much in the same way as the Dadaists.

“Their rapid and raw ways of expression served as a launching pad for punk.”

Steiner reminds us that before becoming a great video artist and one of Switzerland’s best known contemporary artists, Pipilotti Rist played in Les Reines Prochaines, an all-girl punk band. The arrival of video, Steiner points out, offered a liberation from painting, which was very male connotated.

Swiss artists like Rist, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, among many others, invented their own brand of performance art: it was suddenly possible for them to make global art without leaving the country and gain international recognition with a very Swiss identity and sense of humour.

Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich

When Cabaret Voltaire was put up for sale in 2002, Juri Steiner led the “Committee for a Dada House”. Branding it “The Eiffel Tower of Zurich”, the committee helped save the premises from becoming a pharmacy at street level, with luxury apartments above.

“It was quite a feat securing private funds considering that Dada was against bourgeois values, but to us it was essential to preserve the landmark, not only for its historical value, but for the future as well.”

Read more: Dada: the art movement that questioned everything

Cabaret Voltaire reopened in 2004. Since voters approved a swap agreement in 2017 with the owner of the building, Swiss Life Investment Foundation, the Spiegelgasse 1 property in the old town has belonged to the city of Zurich. Cabaret Voltaire is now run by an association and directed by Salome Hohl. Photo Martin Stollenwerk.

A celebration of surrealism

Asked how Surrealism is still relevant to Switzerland today, Steiner answered that although it was officially declared dead in 1969, three years after Breton passed away, both Dada and Surrealism continue to have a profound influence on contemporary artists.

They were very important for the generation of the legendary Swiss art curator, Harald Szeeman (1933 – 2005), twice director of the Venice Biennale and, later on, in the eighties, for Bice Curiger, who founded the magazineParkett (based in Zurich) to promote a transatlantic art connection between Europe and the US.

Curiger went on to be one of the first women to direct the Venice Biennale.

Steiner believes that there is still an enormous interest for movements that emerged in times that are not dissimilar to the ones we are living now:

“We too have a war and tanks on our doorstep and have recently come out of a pandemic. These are key moments that serve to remember and compare. They create the need to dream.”

“Ironically, hard times are good for the arts.”

A new approach

Viewers intrigued by Salvatore Dali’s“Cygnes reflétant des éléphants* [Swans Reflecting Elephants), exhibition Surrealism Le Grand Jeu, photo Etienne Malapert, MCBA

When it came to preparing the centenary of Surrealism, Steiner noted that here have been endless exhibitions in the last 100 years, many by Surrealists themselves, or their heirs. With Pierre-Henri Folon, the MCBA’s contemporary art curator, he decided on the theme Surréalism. Le Grand Jeu (the great game).

The title was borrowed from a short-lived rival group to surrealism, but also as an homage to Marcel Duchamp’s love of chess (see above). Running through the works of the 60 artists on display (including Ernst, Dali, Magritte, Duchamp, Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim and other surrealist icons) are the reoccurring themes of esoterism, automatisms and subconsciousness; the developments in psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud were being followed closely by the Surrealists.

The Lausanne exhibition also celebrates the importance of women artists that were kept at the margins of the official records of the surrealist movement, such as British Surrealist artists Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988) and Marion Adnams(1898- 1995) – see images – as well as British-Mexican Leonora Carrington (1917-2011). In May 2024, one of Carrington’s works was auctioned in New York for the record amount of US$ 29 million. MCBA

Left : Ithell Colquhoun, La Cathédrale Engloutie, 1950

“The great success of the show, in my eyes, is that the works seem timeless. They could belong to the present, the future or the past. Only their frames give them away.”

Plateforme 10: 1 theme for 3 museums

Steiner concludes by highlighting the formidable opportunities offered by Plateforme 10, the recently opened arts complex that unites the fine arts, photography and design museums on the site of the former tenth platform of the Lausanne train station, hence the name.

“Surrealism has been given an echo chamber in our different disciplines.”

“Plateforme 10 is a pioneering project, each museum with a strong identity, working independently, but together. This is very much a Swiss constellation!”

the museum for photography, presents three powerful portrait galleries:

Man Ray, Liberating Photography until 4 August 2024

Man Ray (1890-1976) met the Dadaist, Marcel Duchamp, in New York in 1913. After he arrived in Paris in 1921, he made among the most iconic portraits of the 20th century. (Matisse, Picasso, Coco Chanel, André Breton, Giacometti, Dali, Max Ernst…). His lovers (Kiki de Montparnasse, Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim) became the terrains and partners of his endless explorations into the new field of photography.

One of the three prints of his 1924 photograph of Kiki de Montparnasse, Violon D’Ingres (included in the exhibition) was sold by Christies for $12.4 million in May 2024, a world record for a photograph at an auction.

Cindy Sherman until 4 August 2024

Cindy Sherman (American, 1954) has taken herself since the seventies as her sole subject to question image and identity. Her self-portraitures (she eschews the word selfie) have inspired extravagant and enigmatic portraits.

Christian Marclay x Ecal, Photo Booth (ended 2 June)

Renowned for The Clock that won the prestigious 2011 Venice Biennale Lion d’Or Prize, the ubiquitous Swiss-American artist Christian Marclay worked with the students of Ecal (University of art and design Lausanne) to produce a show that takes portraiture to its extreme (photobooth strips that are presented in original forms).Mudac, themuseum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts showcases Objects of Desire Surrealism & Design, an exhibition by the Vitra Design museum and Alchemy, with glassworks from the Mudac’s contemporary art collection – now the largest in Europe – either created, or inspired by the Surrealists. Until 11 August 2024.

the museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts showcases Objects of Desire Surrealism & Design, an exhibition by the Vitra Design museum and Alchemy, with glassworks from the Mudac’s contemporary art collection – now the largest in Europe – either created, or inspired by the Surrealists. Until 11 August 2024.

Discover more from art-folio by michèle laird

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.